by Karen Jiang

Karen is a medical doctor and a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Riaan Research Initiative. Her husband, Hoong Chuin Lim, is a scientist, and also an advisor to the organization. They are the proud parents of Noah and Marcus, diagnosed with Cockayne Syndrome, and reside in Boston, Massachusetts. Here, Karen tells her story.

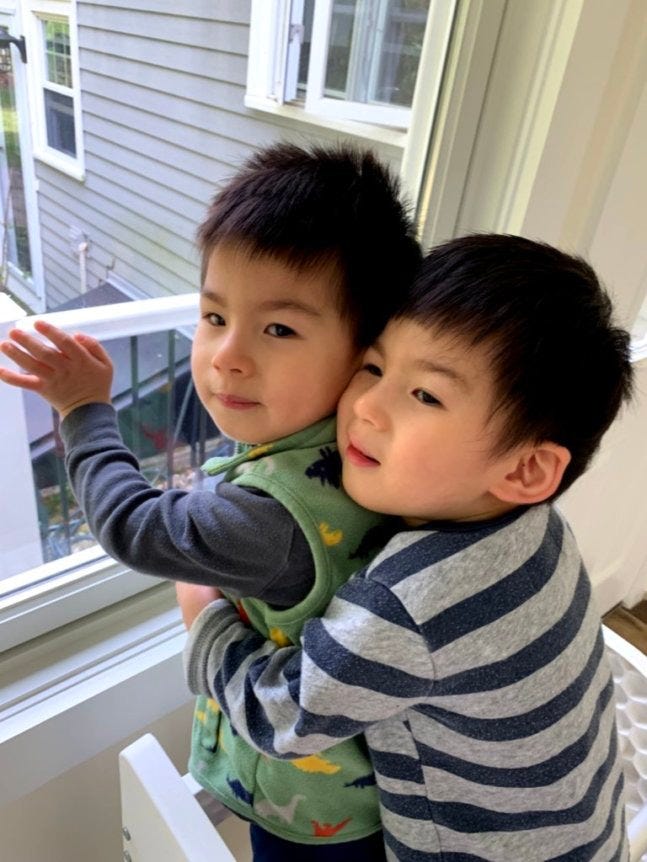

Noah and Marcus were born on September 12, 2018. Their story began before they were even born. At 9 weeks gestation, they surprised their parents that there were two of them on the ultrasound! Neither mine or my husband, Hoong’s, immediate family had twins before. This was too good to be true.

Noah and Marcus were monochorionic diamniotic twins, meaning they shared a placenta but lived in separate sacs. As a result, my pregnancy was considered moderate risk. I was referred to see a Maternal-Fetal Medicine (“MFM”) specialist for close monitoring of possible complications. At 20 weeks, on a routine screening ultrasound, the MFM doctor picked up something unusual. The blood distribution to Noah and Marcus was abnormal. Noah was not getting enough blood, and Marcus was getting too much blood. This was a rare form of Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome, called TAPS (Twin-Anemia-Polythythemia Sequence.) It was even more rare that the boys were diagnosed so early in their gestation.

Marcus was at risk of developing blood clots from having a higher concentration of red blood cells, and Noah might experience poor growth from having anemia. I, as a physician myself, put on a brave face and told myself that complications happen all the time, but kids are resilient. However, the MFM specialist made it very clear that she was concerned. In fact, at the advice of the MFM, we flew from Boston to Baltimore to see a TAPS interventionist for a potential procedure to correct the blood flow. Unfortunately and fortunately, it was decided the risk of this procedure outweighed the benefit, so Noah and Marcus were spared an intrauterine surgery.

Hoong and I returned home and just cried and prayed. Shortly after the Baltimore trip, I also started to experience bleeding because the placenta was covering the cervix (placenta previa). The combination of these complications put the pregnancy at extremely high risk. I still remember the day the MFM walked into the weekly ultrasound room and told us to prepare for the possibility that one or both boys might not make it. I broke down. I think any mother with twins would tell you that once you know there are two of them, you cannot possibly imagine not having either one in your arms. My complications eventually led to a five-week hospitalization until the boys were delivered at 35 weeks, by C-section. Both boys cried in the delivery room. It was a testament that when you wish so hard, with all of your heart, sometimes you can will your children into existence.

Noah and Marcus were in the NICU for three weeks mostly for weight gain. As soon as we brought the boys home, we noticed that something was not right. The boys would not drink milk or formula. They cried and arched their backs through every feed. They also slept poorly, only 20 minutes at a time. At 7 months, they began reflux medications which helped a little bit. Their weights were below the growth curve, and they had gross developmental delays. We always knew that the boys likely had some type of disorder or maybe this was a consequence of the TAPS. Eventually, the boys saw a neurologist who recommended genetic testing. In Feburary 2021, the geneticist told us over Zoom that the boys tested positive for a rare genetic disease called Cockayne Syndrome (CS), and that the average lifespan is 10+ years. What? How can this be? We had fully accepted the possibility of the boys having special needs or lifelong disabilities, but to not watch the boys grow up? To live on this earth without our sweet boys by our sides? This can’t be.

Our world collapsed that day, that week, that month. Hoong and I went into deep anticipatory grief. We were forced to drastically change our vision for the future and to change our priorities. Were we glad that we had learned about this diagnosis? Mostly, because we wouldn’t want to waste a day not loving our boys to the absolute fullest. Having and raising a child would change anybody’s world. Having a child/children with a diagnosis like this uproots your whole belief system and makes you look at life through a whole new, unique and sometimes lonely lens. These days, the four of us enjoy our quiet suburban life. We are evolving everyday and are trying to establish a new routine all of the time. Most people look forward to the future, but the future is scary for us, and we try not to dwell on it.

Five weeks after learning the diagnosis, Hoong and I got connected with Jo Kaur whose little boy Riaan had also just been diagnosed. I, with my medical background and Hoong with his PhD in molecular biology joined efforts with Jo to connect Cockayne Syndrome and gene therapy experts and to expedite the research on the disease. We know that even with our best efforts, there are no promises that we will be able to develop a working gene therapy for our kids in time. However, there is no alternative but to put our best foot forward.

We feel optimistic about the work UMass Chan Medical School has done and will do, and we think if we were to have a shot, this is it. Every family has their own unique vision for what research means for their children diagnosed with Cockayne Syndrome. For us, we would love to have as much time with our boys as possible, even though taking care of children with complex medical issues is no small feat; we would want to take care of them for the rest of our lives if we could. More importantly, we cannot bear the thought that the boys may be in pain as the disease progresses. Any loving parent would tell you that they would take on any pain and suffering in a heartbeat if it meant sparing their children. The reality is there are children with Cockayne Syndrome living with pain and complications as I’m writing this. Our hope is that even if the current research does not lead to “a cure,” it will alleviate the suffering of these innocent children and one day, our children.

Looking back, the TAPS was most likely related to the boys’ genetic mutation as the placenta shares the same genetics as the fetus. Even through this immeasurable pain, we would do this all over again because Noah and Marcus have enriched us and made us better people. We are so grateful that they picked us as their parents.

Thank you in advance for helping this cause and for everyone who has shown up for us during this unimaginable time. We need $4 million to see the research on gene therapy through over the next few years. We would be honored if you made a donation to Riaan Research Initiative. If you prefer, you may also donate offline via check, wire transfer, or another method by contacting info@riaanresearch.org.