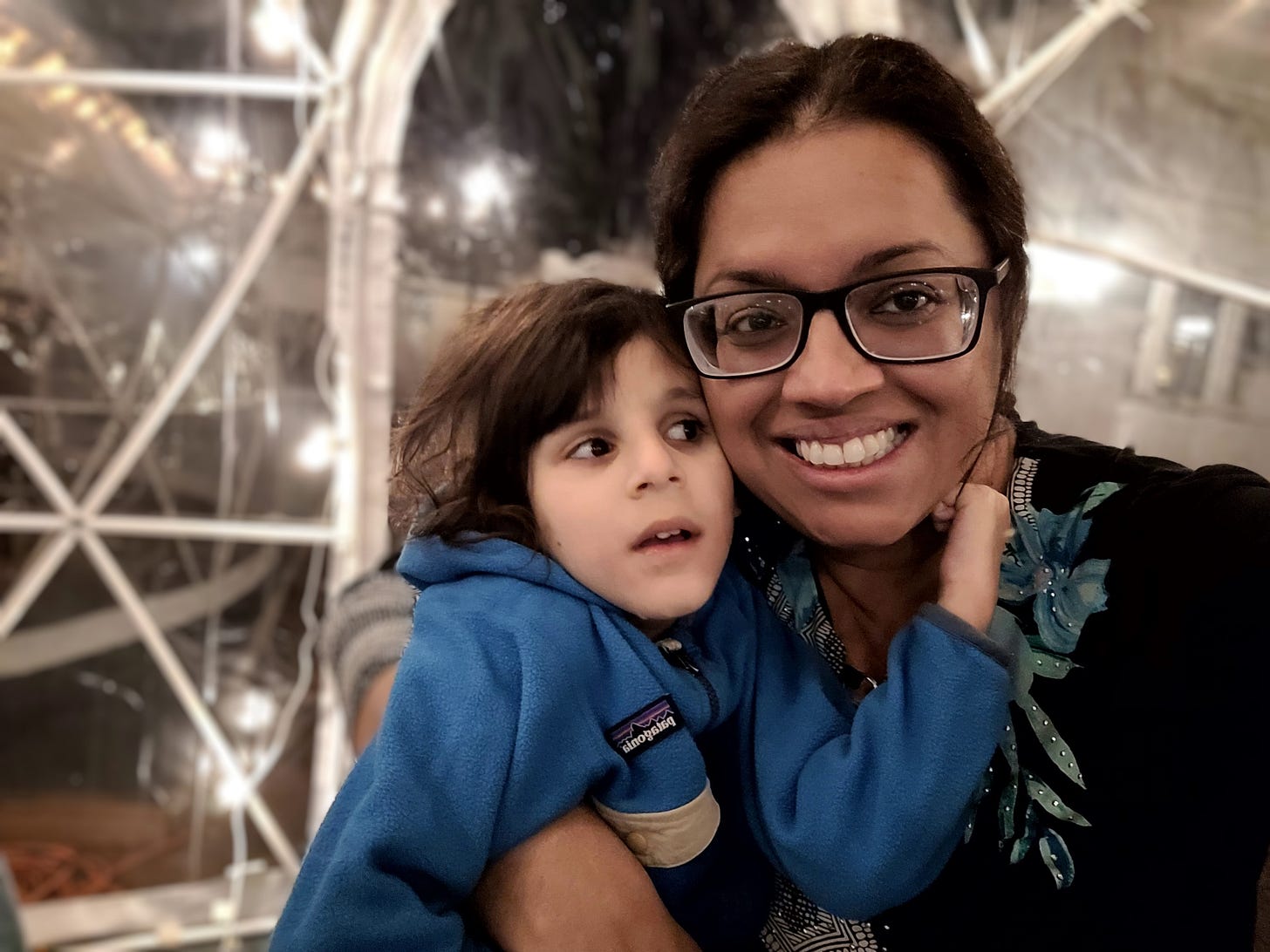

by Jo Kaur, Founder of Riaan Research Initiative

(March 11, 2025) - They say that writing is the deepest expression of the soul. Well, my soul is deeply aggrieved. A gaping wound that’s never healed. But it’s also humbled by the tragedy of life, and deeply grateful for the blessings and joys I do have.

It’s been four years since Riaan’s geneticist cut my heart open.

Cockayne syndrome.

I think about Edward Cockayne sometimes, the doctor who first discovered and wrote about the disease, and wonder again why anyone would want their name affiliated with a disease that kills children, that destroys whole entire universes. A perverse naming practice if you ask me.

As diagnosis day approaches, I’m fluctuating between fatigue and panic. Fatigue because my body is breaking down again: headaches, blurred vision, aches, crying while driving, crying while taking out the trash, and just full on being tired. I’m so tired, I could fall asleep anywhere. This happens every year, climaxing on the anniversary of diagnosis day on March 12th, and lasts until the painful month of March blissfully ends. The body just knows, and sometimes reacts before the mind.

I’m feeling panicked because the rare disease patient advocacy community is facing a significant challenge in funding which could directly impact all of our work. We are all scrambling to figure out what to do as the NIH announces funding caps to cover indirect costs of research and freezes on grants. We know that rare disease programs are often first on the chopping block. It’s as if we’re seeing the summit of Mt. Everest in the near distance only for the mountain to be blown up seconds before we approach.

No rare disease patient advocacy organization could raise enough money to compensate for cuts in government funding to research. The deterrence effect on the next generation of researchers cannot be understated either: who would want to pursue a PhD to research non-profitable diseases like Cockayne syndrome in this climate?

Panic also because Riaan is getting older, and I’m desperate for a treatment. A treatment now. How much faster can we push? How much faster can everything go? I know the team is moving with as much as dedication and urgency as possible. Still, I worry. There’s so much to worry about. We only have so much time. Everything is finite, and we are not as powerful as we think.

Does anyone feel my desperation? I know other parents in the rare disease community must. We shout into the night sky, terrified, and hoping. Hoping, and praying. Doing what we can, but is it enough?

Are we good enough to get a treatment developed? Do we have what it takes?

I think of the words of Terry Pirovolakis, a super dad and inspiration to many of us parents, who was able to get a gene therapy developed for his son Michael in a whopping three years: “These are our children, and we have to save them.”

I took the kids to the playground the other day, feeling bad because they were so bored. The weather was slightly warmer, and I really had no excuse. Forcing down a cup of coffee, taking the twenty minutes to dress them in their winter clothes, we managed to walk to the street and get into the car.

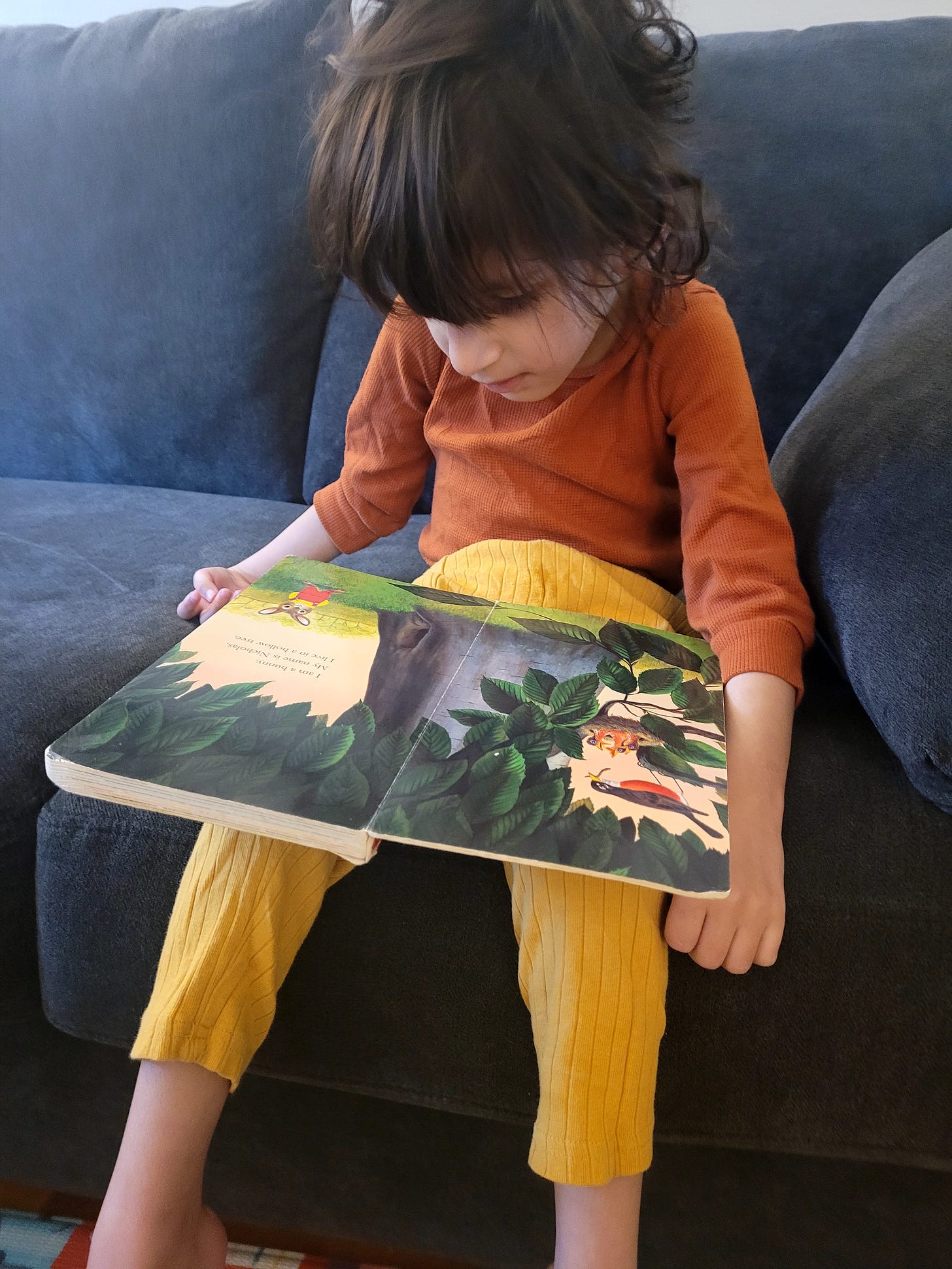

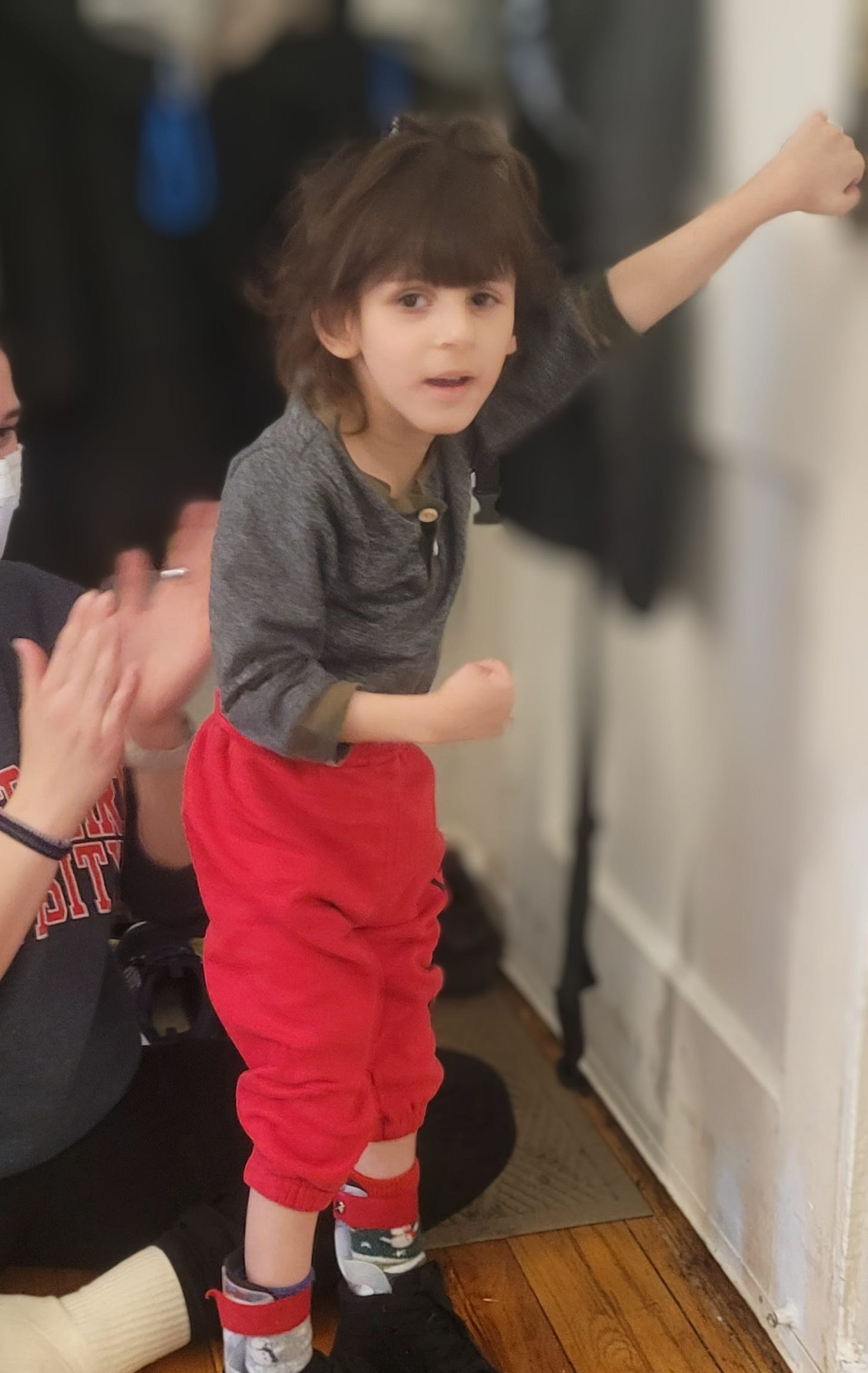

At the park, I put Jivan in the swing, and Riaan cried for me to pick him up from his stroller. Holding him under his armpits, I helped him walk around the playground. He made it easy for a while - bearing weight and taking great steps - but then he crumbled. He’s been making tremendous progress in physical therapy recently, even standing straight and tall on his own, with no help from another person or adaptive device, for a few seconds at a time. Still, it’s hard for him.

Soon the empty playground began to fill with elderly nannies and young children. Everyone was full of energy, and all I wanted to do was sleep. I put Riaan back into the stroller, against his will, and tried to lure Jivan out of the swing with false promises of ice cream while he shouted “NOOOO, MOMMMY.” I locked eyes with one of the super nannies, who gave me a questioning look but then she saw Riaan complaining in his stroller and her eyes filled with sympathy. She’s decades older than me but with so much more energy for young kids. “I’m grieving and my son is cold,” I want to explain. “You don’t understand. Or maybe you do, I don’t know anything about your life.”

It’s been four years since Riaan’s diagnosis but it can still be difficult to see other healthy children running around the playground, full of life no matter the weather, and think about the heavy diagnosis and burden my child faces. How much work he puts in merely to stand for a few seconds a day, or even to eat a meal. How unfair it is that despite his love of life, he faces such a devastatingly short one. These thoughts are foremost in my mind especially as the Cockayne syndrome community has buried yet another child this past weekend, a beautiful and beloved four year-old who died after her feeding tube was dislodged at preschool.

The thought of losing Riaan, of our family’s universe one day ending, pains me greatly. These thoughts feel extremely out of place in this playground full of happy, playful children, deepening my isolation and disconnect.

Eyes tearing up - damn it, not again - my gaze shifted to the vibrant blue sky, and a curious new thought flashed across my mind: How and when will the actual universe end? I have to Google this.

Do you know?

If not, please allow me to indulge you for a moment, and take the scenic route to my ultimate point. But before I do that, let’s set the cosmic stage to give us all some perspective. If you think of how long the universe has existed as one calendar year, humanity appeared only a few seconds before midnight on December 31st. If you think of the entirety of the universe as encompassing all of the grains of sand in the Sahara Desert, then Earth is merely one grain. Or in my terms, humanity is a great wave that rises from the ocean, beautiful and vicious, before it sinks back into the endless sea of the universe.

The prevailing theory about how the universe ends is this: it is headed toward an infinite dark winter, a state of maximum entropy. We know that our world is rapidly expanding, propelled by a mysterious force called dark energy. But as it expands, the stars become more isolated from one another, and conditions for life less possible. Eventually, even protons will cease to exist, and black holes will evaporate. The temperature will reach near absolute zero. Scientists call this the heat death but it’s more akin to the Big Freeze.

However, and this is where it gets really good, even with a dead universe, so to speak, it’s still possible for “something to come (back?) together” and recreate conditions of life. With enough time, a dead universe could even conjure a hypothetical grand piano in the void, or restart the process of galaxies, and solar systems once again. So even in the end, infinite universes are still possible.

In simpler terms, and according to the brilliant cosmologist Kate Mack, “Every moment that’s ever happened in the history of the universe can happen again, an infinite number of times.”

This is just a theory. It’s also possible that the end is just the end, and we only get one shot.

The Big Freeze by the way, if it ever happens, is trillions of years away. For our planet though, we only have about half a billion to a billion years before no life is possible on Earth. Humanity likely has a lot less. Isn’t that sobering?

What are we to make of these mind-bending concepts especially vis a vis our own lifespans, and the extremely short ones our children have? Where does God, and the concept of an afterlife fit into this, especially when the universe inevitably ends? Suffering and disease? Those topics are never far from our minds, especially when you have a child with a fatal disease. Thoughts of a heaven full of beautiful children playing together brings comfort to so many. For others, they believe in the power of combined energy, and forces we do not yet understand. Various other traditions, including my own Sikh faith, invoke concepts of karma and reincarnation, each moment pregnant with value and meaning, the ultimate goal for us to escape the cycle of life and death and to merge with the divine.

And yet some believe there is nothing. That once it’s over, that’s it. End of line.

One such person is Stephen Hawking, who struggled with ALS, a neurodegenerative condition, which caused him to experience severe disability most of his life. Yet despite this or maybe because of it, he transformed the fields of cosmology and physics. He also beat the odds, living over 40 years with a disease that kills most people in 14 months post diagnosis. A staunch nonbeliever in heaven and the afterlife, he thought people should simply live a life where we “seek the greatest value of our action."

Value. How do we define what it is, and who has it?

Many of us, myself included, believe that everyone has great value, no matter who we are or our level of abilities. Our societies and governments are not structured this way, however. As universities and scientists face intense funding cuts, I think of future and/or current rare disease researchers who may pursue a different career because they understandably feel their chosen profession is undervalued and undermined in today’s climate. In the world of medicine and research, rare disease and patients with rare disease are the most overlooked, already facing a significant shortage of resources.

Is it because rare disease patients are considered to have less value in our society?

I think about what people, institutions, and businesses who believe such things might say: Well they’re dying with such severe diseases and there’s so few of them for each disease. Is it worth fighting tooth and nail to try and save them? Is that the best use of our resources?

To answer this question, I think again about our universe, and how it will one day end, and then potentially repeat itself an infinite number of times. I think about value, how we understand, and define it. I think about the courage and strength it takes for Riaan and other children with Cockayne syndrome to live, walk, and be in this world, every day.

Once in a bar in Santa Fe, I met a woman who was a clown. Inspired by Patch Adams, she traveled to hospitals full of sick children around the world to bring smiles to their faces. She loved her job, and was content with her life’s chosen work.

Her soul was at peace, I could see. She said the children did more for her than she could ever do for them. They gave her life tremendous value. They were so sick, fighting these horrible diseases, and yet they tried to smile and laugh with her, to humor her. It was humbling. They had more courage than she’d ever known.

Riaan may never get a PhD in cosmology or physics but he contributes more value to our world than anyone I’ve ever personally known. Riaan and all of his friends in the Cockayne syndrome community do: these children embody and spread the very essence of revolutionary, unconditional love, the most powerful force to exist among intelligent, sentient beings.

Thoughts drifting between the clown and the theories about the ends of the universe, I make my boldest proposition yet.

If children with rare diseases aren’t worth saving, none of us are.

Everything matters, or nothing does. Our kids matter.

An eternal winter of darkness, or a repeat of the magic of creation that flows through all of us? Comforted by the enigmatic possibilities, it is abundantly clear that the hardest, least resourced path to help the most vulnerable is one well worth pursuing.

Child patients with rare diseases represent universes we can save, destinies we can alter. So let’s do it. What better time than now, when the odds are against us? There’s a universe where we get it right, where we build the cures, and defeat the odds. Maybe that time and place is now.

Let’s build these treatments and work hard to pour our limited resources into them. To the researchers, clinicians, and institutions who fight for us, who stay in through the madness, who work overtime to protect the most vulnerable including children with rare diseases, thank you. To our donors who help conjure miracles in the void, you’re our greatest treasure. You have no idea how grateful we are for you.

As our universe continues to expand across the cosmos, heading toward the unknown, I continue to put my faith in the most precious manifestation of the divine that I have personally encountered: my Riaan.

Through him, the possibilities are endless.

***

We need you. Our costs have risen. Every dollar donated helps. Please make a tax-deductible donation today to Riaan Research Initiative here, and help us continue to fund the development of a potentially life-saving gene therapy for Cockayne syndrome.